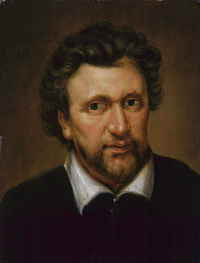

How Ben Jonson's poetic masterpieces found the world by leaving it behind.

Washington, Hollywood, Wall Street, the Pentagon: These names have a social meaning apart from geography. Each one indicates a certain world of activity?and the word world, in its primary sense, refers not to a planet but to the realm of human doings. The dictionary tells me that the Old English "weoruld" means something like "human life" or "age of man."

Washington, Hollywood, Wall Street, the Pentagon: These names have a social meaning apart from geography. Each one indicates a certain world of activity?and the word world, in its primary sense, refers not to a planet but to the realm of human doings. The dictionary tells me that the Old English "weoruld" means something like "human life" or "age of man."

Worldly has an ambiguous, shifting place on the scale from negative to positive adjectives. To be unworldly might signify being a dupe, and worldly knowledge is desirable. Too much worldly knowledge, though, may suggest a villain played by Alan Rickman.

Those good and bad connotations are epitomized by another place name that, in 16th- and 17th-century England, was a synonym for "the world" in the urbane, social sense: the royal court. In Ben Jonson's time, the court was all of the above. It was Washington and Hollywood, the Pentagon and Wall Street, and more: a single seat of all kinds of power, concentrated in a few buildings in one city, a worldly magnet attracting all the most ambitious, gifted people in the worlds of art, money, politics, religion, sex, learning, and glamour. The court embodied worldliness at its most alluring and at its most treacherous.

To want to renounce such a world, to leave it behind, is a recognizable impulse. Most of us have felt it. But "us" needs to be qualified: Renouncing the world is also a luxury. You need to have a place in the world to think of leaving it behind for higher or more spiritual things.

That truth helps explain why Ben Jonson's poem about leaving the world is in the voice of a "gentlewoman" who is not simply "virtuous" but "noble." In the course of her life, she has been in a position to observe the world (which, for her, has been the court). Her privileged worldly position allows her speak this wonderful and stoical goodbye. (A goodbye that the contentious Jonson?he killed a man in a duel and wrote many an angry epigram? assigns to this woman rather than pretending to claim it for himself.)

Does the poem have to do with another sense of leaving the world, actual death? I think so, and much of the poem's accumulating power, for me, is in the energy generated by different senses of "the world" and "farewell." Jonson's poem is so plain, so direct and explicit, that a reader might miss its overtones of mystery and mortality.

I mean, for example, the way her argument seems both to reverse itself and to intensify its original course in the final 16 lines, beginning with "But what we're born for, we must bear." Here, the fiercely independent moralist who has been contemptuous to the point of seeming paranoid says that her situation is universal and must be endured: "Else I my state should much mistake,/ To harbor a divided thought/ from all my kind; that for my sake,/ There should a miracle be wrought." Her sense of human mortality?she is no suicide, but she is closer to the end than the beginning?is tied to her sense of having human, mortal desires for the world and its goods.

After the fourth line's metaphor, "My part is ended on thy stage"; after the subsequent military images ("to tread/ Upon thy throat") and visions of the world as a strutting, overdressed floozy or a deceitful retailer; after comparing herself with trapped animals escaping cages or snares, the gentlewoman simultaneously calms down and increases her resolve: She abandons even the world's figurative language in favor of relatively calm, plain speech. "Scorn" and "false relief" are splendidly clear and explicit. She has effectively left the world, and in the last few lines we feel her leaving off her rant against the world as well.

"To the World: A Farewell for a Gentlewoman, Virtuous and Noble"

False world, good-night! since thou hast brought

.?That hour upon my morn of age,

Henceforth I quit thee from my thought,

.?My part is ended on thy stage.

Do not once hope that thou canst tempt

.?A spirit so resolv'd to tread

Upon thy throat, and live exempt

.?From all the nets that thou canst spread.

I know thy forms are studied arts,

.?Thy subtle ways be narrow straits;

Thy courtesy but sudden starts,

.?And what thou call'st thy gifts are baits.

I know too, though thou strut and paint,

.?Yet art thou both shrunk up, and old,

That only fools make thee a saint,

.?And all thy good is to be sold.

I know thou whole are but a shop

.?Of toys and trifles, traps and snares,

To take the weak, or make them stop:

.?Yet art thou falser than thy wares.

And, knowing this, should I yet stay,

.?Like such as blow away their lives,

And never will redeem a day,

.?Enamour'd of their golden gyves?

Or having 'scaped shall I return,

.?And thrust my neck into the noose,

From whence so lately, I did burn,

.?With all my powers, myself to loose?

What bird, or beast is known so dull,

.?That fled his cage, or broke his chain,

And, tasting air and freedom, wull

.?Render his head in there again?

If these who have but sense, can shun

.?The engines, that have them annoy'd;

Little for me had reason done,

.?If I could not thy gins avoid.

Yes, threaten, do. Alas, I fear

.?As little, as I hope from thee:

I know thou canst nor shew, nor bear

.?More hatred, than thou hast to me.

My tender, first, and simple years

.?Thou didst abuse, and then betray;

Since stirr'dst up jealousies and fears,

.?When all the causes were away.

Then in a soil hast planted me,

.?Where breathe the basest of thy fools,

Where envious arts professed be,

.?And pride and ignorance the schools:

Where nothing is examin'd, weigh'd,

.?But as 'tis rumour'd, so believed;

Where every freedom is betray'd,

.?And every goodness tax'd or grieved.

But what we're born for, we must bear:

.?Our frail condition it is such,

That what to all may happen here,

.?If't chance to me, I must not grutch.

Else I my state should much mistake,

.?To harbor a divided thought

From all my kind; that for my sake,

.?There should a miracle be wrought.

No, I do know that I was born

.?To age, misfortune, sickness, grief:

But I will bear these with that scorn,

.?As shall not need thy false relief.

Nor for my peace will I go far,

.?As wanderers do, that still do roam;

But make my strengths, such as they are,

.?Here in my bosom, and at home.

?.?.?................?.?.??Ben Jonson

Click the arrow on the audio player below to hear Robert Pinsky read Ben Jonson's "To the World: A Farewell for a Gentlewoman, Virtuous and Noble." You can also download the recording or subscribe to Slate's Poetry Podcast on iTunes.

Slate Poetry Editor Robert Pinsky will be joining in discussion of this poem by Ben Jonson this week. Post your questions and comments on the work, and he'll respond and participate. You can also browse "Fray" discussions of previous classic poems. For Slate's poetry submission guidelines, click here. Click here to visit Robert Pinsky's Favorite Poem Project site.

Former Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky is Slate's poetry editor. His Selected Poems is now available.Source: http://feeds.slate.com/click.phdo?i=2403e79c173e41ad0f14680bbbcf6793

sarah jessica parker erik bedard ing direct nostradamus melaleuca kelly brook antonio cromartie

0টি মন্তব্য:

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন

এতে সদস্যতা মন্তব্যগুলি পোস্ট করুন [Atom]

<< হোম